By Jessica Johnsrud, Education Coordinator and Assistant Director

As the busy fall season winds down, I am able to take time to review the bat survey data that Woodland Dunes helped collect for the DNR this summer. Woodland Dunes has a device that can detect and record the echolocation calls of bats and mark the GPS coordinate where each sound was intercepted. This information is uploaded to the computer and transferred to the DNR who then interpret the data. A trained biologist is able to identify the bat species recorded by reading the visual representation of each sound, known as a spectrogram. Just like each bird species has its own set of calls and sounds, so does each bat species.

As the busy fall season winds down, I am able to take time to review the bat survey data that Woodland Dunes helped collect for the DNR this summer. Woodland Dunes has a device that can detect and record the echolocation calls of bats and mark the GPS coordinate where each sound was intercepted. This information is uploaded to the computer and transferred to the DNR who then interpret the data. A trained biologist is able to identify the bat species recorded by reading the visual representation of each sound, known as a spectrogram. Just like each bird species has its own set of calls and sounds, so does each bat species.

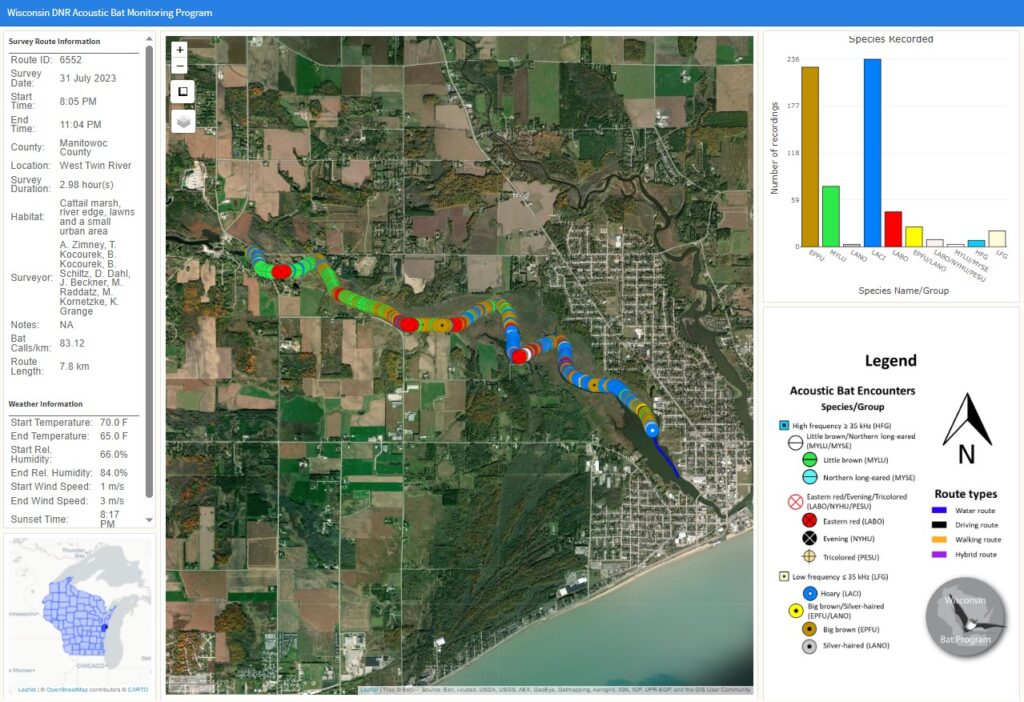

After the spectrograms are identified, a map is created which includes the survey route and the points where bats were recorded. We have collected data on as many as seven routes in some summers, when the weather cooperates and schedules allow. At a minimum, we do three routes, once of which is on the lower section of the West Twin River.

This survey is always the most enjoyable and relaxing of the season. It’s a “posh” experience because a very generous couple donates their pontoon boat and even drives us. This survey is also the most fruitful, detecting more bat species and individuals than the routes we walk in the preserve or nearby green spaces. This is likely because after sleeping all day, bats fly out of their roosts and are hungry and thirsty. Foraging for insects near the river or other body of water will meet both of these needs. The results of this summer’s survey on the river recorded five bat species: big brown, little brown, silver-haired, hoary and red.

Woodland Dunes has been conducting bat surveys since 2013 and people may wonder why this important. Many bats are insect eaters making them major predators of agricultural pests and biting insects that transmit disease like West Nile. One bat can eat up to 1,000 mosquitos in an hour and about half its body weight each night! It is estimated that bats save United States farmers approximately $22 billion each year in reduced crop damage and limiting the need for pesticide use. These are amazing ecosystem services!

Unfortunately, bats that hibernate in caves, mines or buildings, have been severely impacted by an invasive fungus that grow on bats’ wings and face during hibernation. The disease is aptly named white-nose syndrome and causes bats to wake up more than usual during the 6-8 month hibernation period, using up precious fat reserves and eventually causing death. The little brown, big brown, Northern long-eared and tricolored (formerly known as Eastern pipistrelle) bats are the cave bats in Wisconsin. I am always extra excited when we received bat survey results and see any of these species.

The data we and other organizations and individuals collect helps provide scientists with more information about bat populations and can help inform management decisions for these amazing mammals. Some bat populations may be starting to slowly bounce back from white-nose syndrome and forms of treatment are being explored, especially for the most vulnerable of the hibernating bat species.

Bats are wonderful, essential parts of our natural world. Learning about them, and helping them as a result, will be good for nature, and ultimately ourselves as well.