One of this year’s projects for Woodland Dunes has been to improve the mouth of a basically unknown little stream which long ago was known as Forget-Me-Not Creek. This site also happens to outfall to Lake Michigan at the location of the Spirit of the Rivers sculpture along Memorial Drive. The creek was supposedly named for the forget-me-not flowers which were planted along it’s banks by an early German settler. Over the years the creek had become partially blocked by rock and shrubs, some of which were non-native invasives, making the passage of migratory spawning fish more difficult. Much of the creek’s watershed lies within the Woodland Dunes preserve, and native fish are an important part of both our local terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, so we want to do what we can to encourage free movement of fish in the spring when many move inland to spawn.

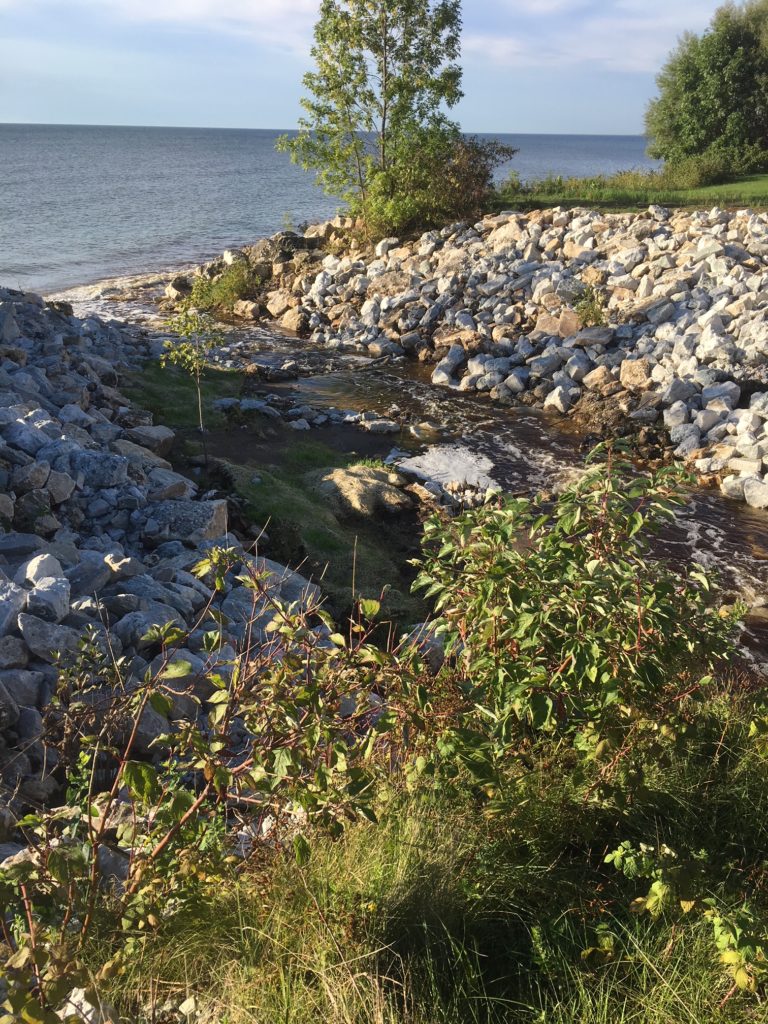

So, if you’ve visited the wayside next to the amazing Spirit of the Rivers sculpture, you’ve seen that the mouth of the creek has been changed. The existing stone and brush was removed, the creek widened and a small floodway created, and then stone was again placed to form riffles and pools and to stabilize the banks. Now the banks are being replanted with native shrubs and trees only, and the floodplain seeded with native wetland plants. After the dedication, some of the upland areas will be seeded with native prairie grasses and wildflowers, as will the top of the bluff where we will preserve the abundant milkweed for monarch butterflies. As is always the case, the site was severely disrupted by our excavation but it will heal again and we will make sure to stock it with beneficial plants. Like the sculpture next door, it will be a creative endeavor, and a work in progress for years.

It is interesting to re-plant an area like this, to come up with some kind of vision or goal as to what a site should be. Along the Lake we are fortunate to have nearby Woodland Dunes, Point Beach State Forest, and the Rahr School Forest, each having remnants of the native vegetation of our lakeshore. It’s impossible to duplicate the degree of diversity of plantlife in these places- we would need to install more than 400 species of plants. Like with so many things we will begin with species which are easy to obtain and grow, and add diversity from there. After plants go in the ground, they need tending to – in this case involving my less than graceful attempts to clamber over the rocks to water and mulch the plants. I am counting on the preoccupation of visitors to the site with the nearby sculpture rather than my profound lack of grace and balance. Fortunately our recent rain has made watering unnecessary for the near term.

Then there is the placement of stones in the creek bed. The riffles, or shallow rocky areas are subject to adjustment, which reminds me of playing in the river when I was a kid. The water flow varies from day to day, as does the way water moves through our little stream system. The beauty of being down in the stream itself is that you become aware of the creatures which so quickly expand their territories into new areas- in just a day or two green frogs began to appear, and water striders. It will be interesting to sample the bottoms of the pools for invertebrates as time passes.

Perhaps the most interesting so far was a mink which showed up one morning as I happened to be checking things. Mink and other weasels always seem to me to be particularly graceful, and this beautiful dark brown animal flowed over and under the rocks along the bank. Eventually it reached the large concrete culvert which guides the stream under Memorial Drive. The mink stopped for a few seconds, then dove into the water at the pool next to the culvert, swam up to and over the culvert’s edge just like a sucker during the spring run. Then it swam up into the culvert and under the road, I assume headed to the woods behind Aurora’s hospital. I’ve seen several mink that had been unfortunately flattened on Memorial Drive this year, and I’m glad that this one has figured out a safe way to cross the road. In fact, that culvert is large and flat enough at the bottom to allow for a lot of animals, not only fish, to pass. Roads are one of the greatest hazards to wildlife, and at least here there is a safe connection between our stream mouth and the woods to the west.

Like most habitat restoration projects, this will be ongoing and change over time. We’ll learn what works and what doesn’t, and tweak things a number of times. We are glad that the Spirit of the Rivers steering committee asked us to be a part of this, especially because the sculpture honors the native people who lived here longer than we have. And, we’re impressed that Mr. Wallen has such a thorough understanding of the nature of this area and wanted it be a part of the project overall. We are also grateful to the Fund for Lake Michigan and US Fish and Wildlife Service for funding towards the stream project and native plantings around it.

We’re sure this project will help wildlife, and also be an enhancement to Manitowoc and Two Rivers as an attraction for visitors. We can’t wait to see what happens as the site matures over time, but it certainly looks like a win for both the community and wildlife.