This week’s Ripples was written by Anna Hall, Woodland Dunes Intern from Silver Lake College

Early this morning, I had the privilege of witnessing an American Woodcock searching for food in the front yard of the nature center. This is an uncommon sighting simply because woodcocks tend to spend the majority of their time hidden deep within fields and forests; they very seldom are seen out in the open. This woodcock was drawn out of his typical environment because of the large snowfall our area recently experienced, and he had to get creative about finding food.

American woodcock in snow

In order to feed, woodcocks require soft, exposed soil. They have a long bill which they use to probe into the ground in their search for little critters to eat. By far, this bird’s favorite meal is a healthy helping of earthworms.

Worms are high in both protein and fat, and comprise about three-quarters of the woodcock’s diet. One difficulty these birds may experience in their quest to find food is if after they have returned north in the spring, the area experiences late snow or the ground freezes solid.

When it comes time for the woodcock to breed, the males establish singing grounds. Their courtship dance is truly beautiful to see. The male will begin by emitting a buzzing sort of sound called peenting while he is on the ground. After a minute or so, he flies up into the air and hovers in a circle high above the ground. His descent pattern is quite interesting; after he is finished hovering, he will swoop down in a spiral as he sings a warbling call. When he comes to rest on the ground, he begins this dance all over again.

The female woodcock nests close to the singing ground where she mated. She is quite the independent lady, as the male plays no role in the nesting or rearing of the young woodcocks. The females favor nesting sites with plenty of ground cover and opportunities for camouflage. If the female woodcock is disturbed during the incubation period of the eggs, she may abandon the nest. However, the longer she stays on the eggs, the less likely she is to leave her unhatched babies.

All hatched birds can be categorized as either precocial or altricial. Precocial means they are relatively independent soon after hatching, and altricial means they require more extended care from their parents. Woodcocks are precocial; the young birds leave the nest just a few hours after hatching, and can successfully leave their mother after just six weeks.

As I continued to watch this woodcock prod the cold soil, I was struck by the beauty and intelligence of this deep forest creature. Its ingenuity and perseverance had me rooting for him to find some form of sustenance in the snow-covered ground. When he finally tugged an earthworm free, my hope that he would live to sky-dance and sing was renewed.

If you’re interested in seeing the woodcock’s courtship dance, join us for our Spring Twilight Trek at Woodland Dunes on April 27th (call for more info), or keep an eye out for this bird’s evening twirling at a forest edge or field near you.

photo taken by Nancy Nabak, Communication and Development Coordinator

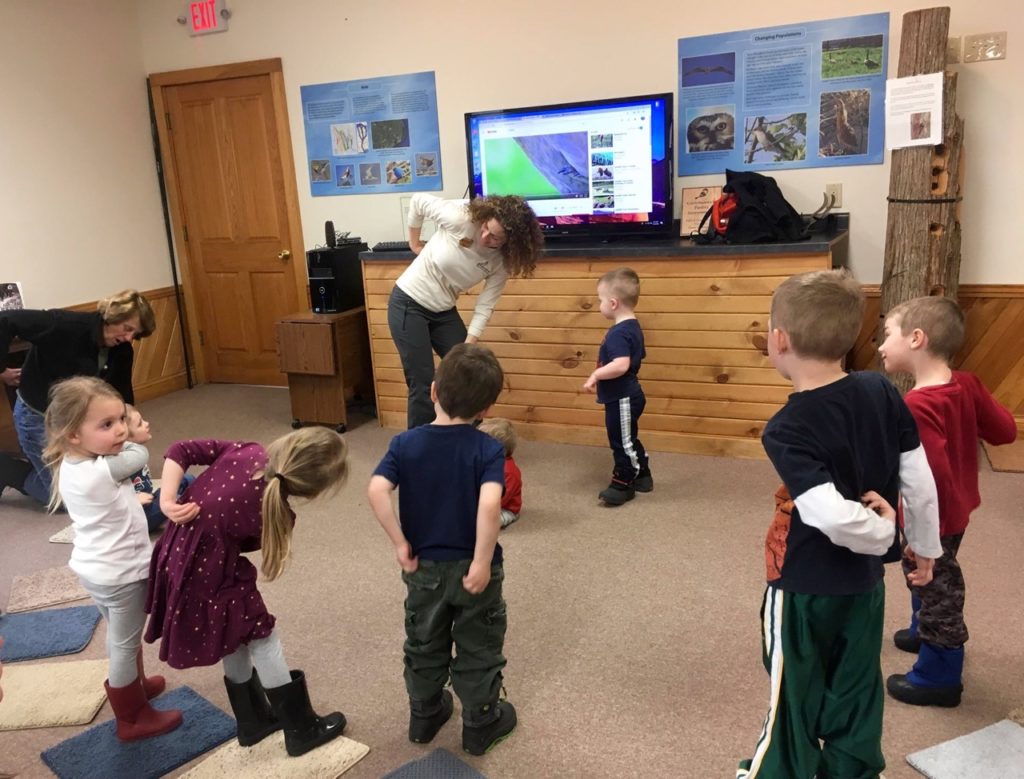

Preschoolers preening like cranes

Preschoolers preening like cranes

caused their eggs to become brittle and easily broken. When I was young, ospreys and bald eagles were rare in Wisconsin. Fortunately, people cared enough about these animals to require that alternatives to DDT be used, and over the years the birds increased in population. Now, it’s not uncommon to see eagles here year round, and ospreys in the summer.

caused their eggs to become brittle and easily broken. When I was young, ospreys and bald eagles were rare in Wisconsin. Fortunately, people cared enough about these animals to require that alternatives to DDT be used, and over the years the birds increased in population. Now, it’s not uncommon to see eagles here year round, and ospreys in the summer. that they could plan for replacing lighting without disrupting the nesting birds, and indeed the lights were replaced in fall long after all the birds had left. However, their old nest had to come down with the old lights, and there was concern about what would happen when the birds return this spring. Neighborhood residents who had watched the birds in past years were also concerned that they would be displaced. Fortunately, the Two Rivers Parks Dept. was open to discussing the possibility of placing a separate nesting platform for the birds, and Steve Lankton, who is very interested in raptors, offered to donate the funds needed for the project. Moreover, Two Rivers Water and Light was willing to put up the pole and platform, which was built at Woodland Dunes.

that they could plan for replacing lighting without disrupting the nesting birds, and indeed the lights were replaced in fall long after all the birds had left. However, their old nest had to come down with the old lights, and there was concern about what would happen when the birds return this spring. Neighborhood residents who had watched the birds in past years were also concerned that they would be displaced. Fortunately, the Two Rivers Parks Dept. was open to discussing the possibility of placing a separate nesting platform for the birds, and Steve Lankton, who is very interested in raptors, offered to donate the funds needed for the project. Moreover, Two Rivers Water and Light was willing to put up the pole and platform, which was built at Woodland Dunes.