Submitted from the archives by Nancy Nabak, communication coordinator

Submitted from the archives by Nancy Nabak, communication coordinator

We start this month with another look back at our beginnings. Today, we harken back to September, 1976, when the following was included in our 5th Dunesletter.

“Friends and Nature Lovers,

We gather here today, August 12, 1976, for a few moments to dedicate and forever name a beautiful place in Woodland Dunes.

We honor a wonderful and beautiful person and friend. Our great and nature-loving friend, Sister Teresita Kitel, whom we all love and whose great knowledge of natural things and unselfishly dedicated work over the many years for human beings and their environment has been most remarkable.

Sister Teresita is one a kind who has shared her wisdom with thousands. A great teacher, a great environmentalist, a great leader and ‘our great friend.’

Sister Teresita, you have surely met God’s challenge and directive with your teaching and educating man to understand, appreciate, preserve and conserve his environment.

Therefore, in recognition and honor of your great work – from this day on here at Woodland Dunes this spot on which we now stand shall be known as “Teresita Knoll” and in the name of the membership and officials of Woodland Dunes I have officially named and dedicated it.” – Herbert Vander Bloemen, retired Conservation Warden.

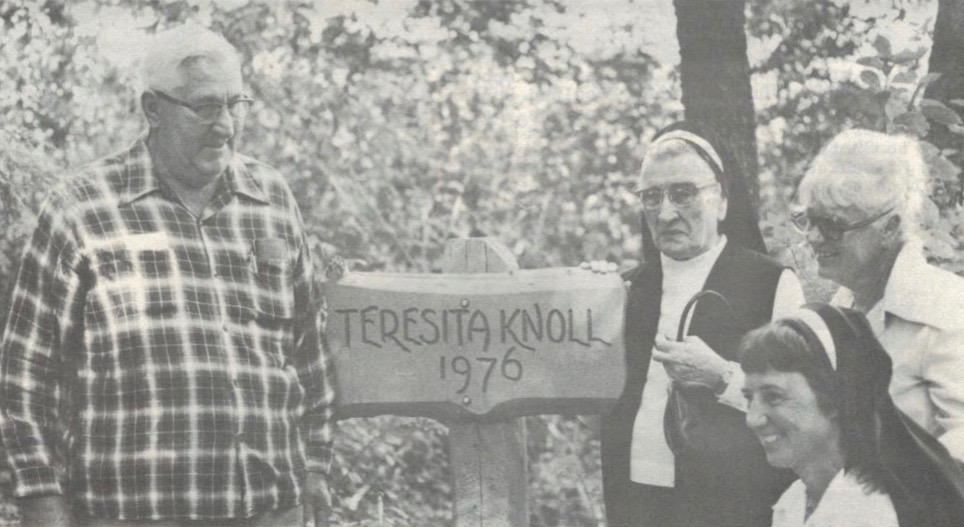

Photo: Left: Herbert Vander Bloemen, Sister Teresita, naturalist Winnifred Smith, and Sister Julia Van Denack, Conservation Education, Inc. president. Teresita Knoll is adjacent and to the east of the “Bicentennial 40” on Black Cherry Trail. Copy and photo circa 1976.