Contributed by Nancy Nabak, communication coordinator

Last week we shared a story from our March 1978 Dunesletter, which was received with great enthusiasm. This week, we are staying with that issue and sharing the original Ripples from that newsletter, written by A.G. OLIUS.

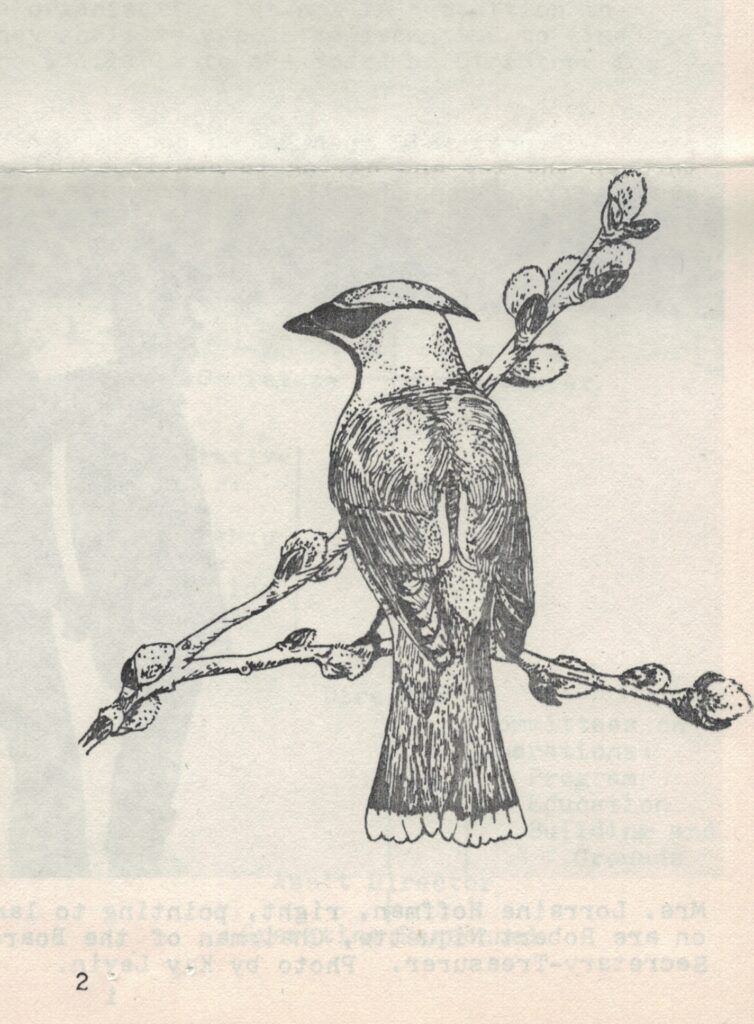

“Silvery-grey pussy willows are familiar harbingers of spring. By the time the exquisite gold-spangled staminate blossoms are fully developed, however, they are generally overlooked… out-rivaled by their wetland companions, the marsh marigolds.

The pussy willow is a member of a family that also includes the various poplars. Both the pollen and seed-bearing flowers of these trees appear in tassels knows as aments, more commonly called, “catkins.” The male and female flowers are borne on separate plants, with rare exceptions.

Because they flower so early in the spring, willows are prepared for encounters with weather. Flowers are formed under the single bud scale.

As the flower cluster begins to grow, with the first warm rays of spring sunshine, it pushes back the waxy scale, but is further protected from damage by wind and bright sunlight with hairs which tip the flowers. In this stage they are the well-knows willow “pussies.”

As the season progresses, pollen-dusted stamens on the male trees reach out from their fur-bordered scales, while on the female trees, each fur-ringed scale of the greenish catkins thrusts our Y-shaped stigmas.

Nectar-seeking insects and wind carry pollen from staminate trees to the stigmas of the pistillate ones. Bees search out the early spring bounty of pollen and the honey supply from the nectar, which is produced at the base of the catkins. These attractive “goodies” assure pollination, in addition to wing-borne encounters.

In June, the willow seeds are ripe. The pistillate catkins are then made up of numerous tiny pods, filled with seeds, each equipped with a fuzzy parachute, forming “willow cotton” which drifts off with the wind. The staminate catkins have long-since withered and fallen to the ground.

Willow seeds retain their ability to germinate for only a few days, and under the right conditions do so immediately. The multitudes of their kind would soon crowd out other species in the forests, except that they need extra bright light. For this reason, they are pioneers in sunny wetlands, or often move in after burns or clearing of the land.

Willows hybridize readily. The lineage of a willow “pussy” may be as questionable as a stray cat’s litter of kittens.”

Artwork by Mary Beth Prondzinski